Kyle on Halifax

You will be ever seeing but never perceiving

Last month Emily, Lydia, and I took a trip east on the Trans-Canada Highway from Quebec to revisit some of the places I lived while on my Mormon mission.

And, when Greg or my mom or Tyler would ask about the trip (“How was the trip where you return to your mission going, Kyle”), I’d find myself at a loss for words. This was a problem when we were planning the trip. I found my reasons for going hard to place.

The first day in Quebec City I woke up with a swollen, blood-shot eye and a scratchy, lumpy feeling in the back of my throat. I called a physician to the hotel and he prescribed me some eye vaseline and left the throat to clear on its own.

“It was good that you called,” he said as he wrote out the receipt.

“Oh?” I said, “I wasn’t sure if I was overreacting.”

“Americans,” he said, “it would have gotten worse.”

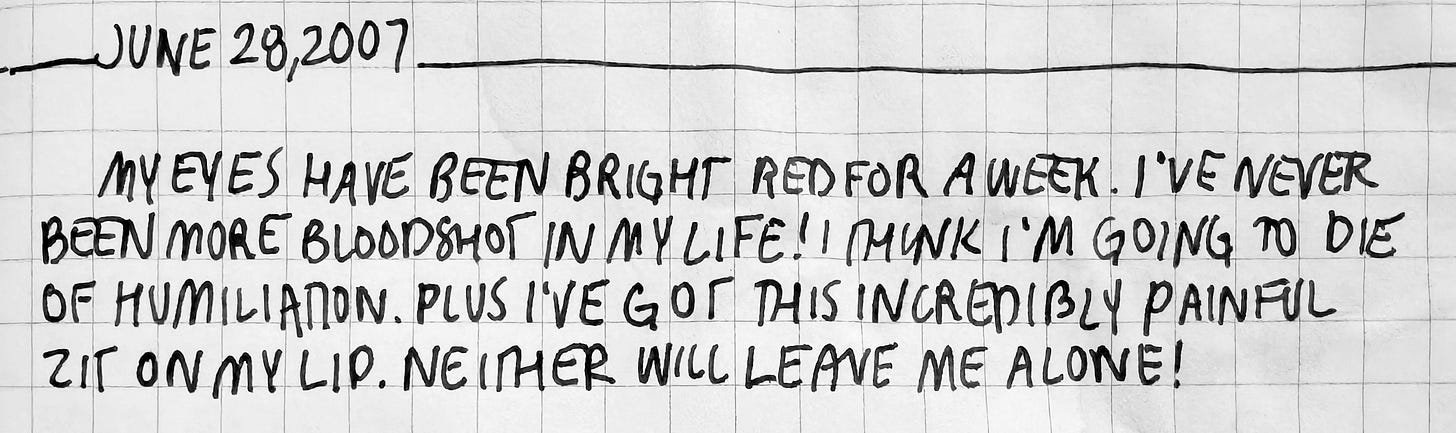

In my second week at the Missionary Training Center, in 2007, I woke up to swollen, blood-shot eyes. I tried some Visine from the small store in the center of the campus. It didn’t work. There might have been a nurse or doctor on call, but I didn’t know to ask for one. All my life we just called grandpa.

On Sunday at church, the branch president noticed my eyes and brought me into his office for an examination. He was an optometrist. He wrote up a prescription and my eyes cleared up soon after.

Missionary work is eyes work. It’s flirty, soul gazing work. Maybe it’s like being a waiter, or a flight attendant (I imagine). After a few months of doing missionary work you get trained to read faces: are they open to us? Would they entertain a conversation about Jesus on the street?

“I think we’d be good missionaries,” I say to Emily.

“Yeah, I think we were.”

“No. Sorry, I mean now. I think I know better when people are just being nice. I thought I could talk people into Mormonism.”

“Yeah, my only converts were lonely grandmas. They wanted to join the Russian grandma social club.”

Quebec City was new to me and Emily, but it reacquainted me with the French language (and my unknowing of it). Half of my mission was in parts of French New Brunswick, just a few miles to the south.

In a cafe, I wait for a cappuccino, while the two men in front of me say “fromage, fromage, fromage” back and forth. They say it knowingly, and then they laugh. I’m playing a language learning game where the sims are only allowed to say the one word I know.

Missionary work is talking work. It is clear your throat, open your mouth, and hope something comes out work. Sometimes, when we would stop people on the street, they would pretend to only speak French.

“Fromage, fromage, fromage” they would say.

Then Tyler would say “I speak French” (in French) and he would always say it even knowing that it was the last thing in the world they wanted to hear.

Later, present day, a few days into the trip, we’re in half-French New Brunswick (a place where I can order coffee without loudly offering “HELLO” first). And, I see a t-shirt in a grocery store that says ROAM FREE and I read it as FROMAGE.

“Maybe I’m dialectic” I say to Emily. She says “you mean dyslexic.” Just kidding again our relationship isn’t like an ongoing Who’s On First bit. We talk like everyone else (baby talk)!

“Why aren’t I nostalgic about anything?” I ask Emily (several times). She says “I think you mean agnostic”. Just kidding, she didn’t say that (she said it with a baby voice).

After a few hours we arrive in Fredericton. The city has grown—new chain stores south of the freeway, and a beautiful little contemporary museum downtown. It is Fredericton as I remember it, only it isn’t the Fredericton I remember that we’re returning to. Memories are coming back—little vignettes of chatty stranger’s living room couches and long walks with silent missionaries down snowy sidewalks.

But a lot of my memories feel stale and empty. Somehow less real. It’s hard for me to believe they really happened in this sprightly little town.

“There’s no there, there” Emily offers from Gertrude Stein.

By the morning of day seven, my prescription eye vaseline has done its work. We drive through the thick forest green of New Brunswick. In this place, trees grow like weeds and clouds loud the sky. Everything is extra alive.

We spend the last few days of the trip at a perfectly charming bed and breakfast in Halifax. The hosts, Liz and David, are Irish immigrants who feel like time travelers from our future. They make long eye contact and speak their minds. Their books are our books, and their daughter out in Calgary is 28 now (as old as the bed and breakfast). They give us good recommendations for dinner, and we bond over our shared love for the essentials (bread and coffee).

Liz is a great listener and conversationalist. I tell her about my time in Halifax, about being a missionary.

“Isn’t it wonderful she’ll have a life without any of that?” she asks over oats, fruit, and french press coffee on the last day. Having just toured my glory days with my wife and baby, I’m surprised to feel like she’s right.

On the last night she calls us downstairs to have ice cream and say goodbye. Lydia crawls freely around the kitchen, pulling up to lean or touch Liz’s bare feet. We say goodnight and she says she’ll see us in Oakland one day.

In the morning, we grab an early cab and find a note from her on the door that says “safe travels beautiful family”.

Emily and I talk on the plane about the how big it is to care—to love and be loved. We’re talking effortlessly. Twelve hours of traveling passes by easily. The past is metabolizing, becoming fuel for what’s next.

My throat feels clear.

Beautiful

Perceptive as usual for you, thoughtful and introspective. Our past is always present and makes us what we are and what we think. Glad you got your eyes fixed - sorry you didn't call grandpa tho. Glad you got to revisit places important to you - I've found that when I've done those things that feelings always come and places seem somehow smaller to me. Strange.